I recently had the chance to visit World Without End (https://caamuseum.org/exhibitions/2024/world-without-end-the-george-washington-carver-project) at the California African American Museum, an exhibition devoted to George Washington Carver’s legacy as both an artist and an innovator. The show reframed Carver not just as “the peanut guy” of popular imagination, but as a visionary who pioneered sustainable practices long before the term existed.

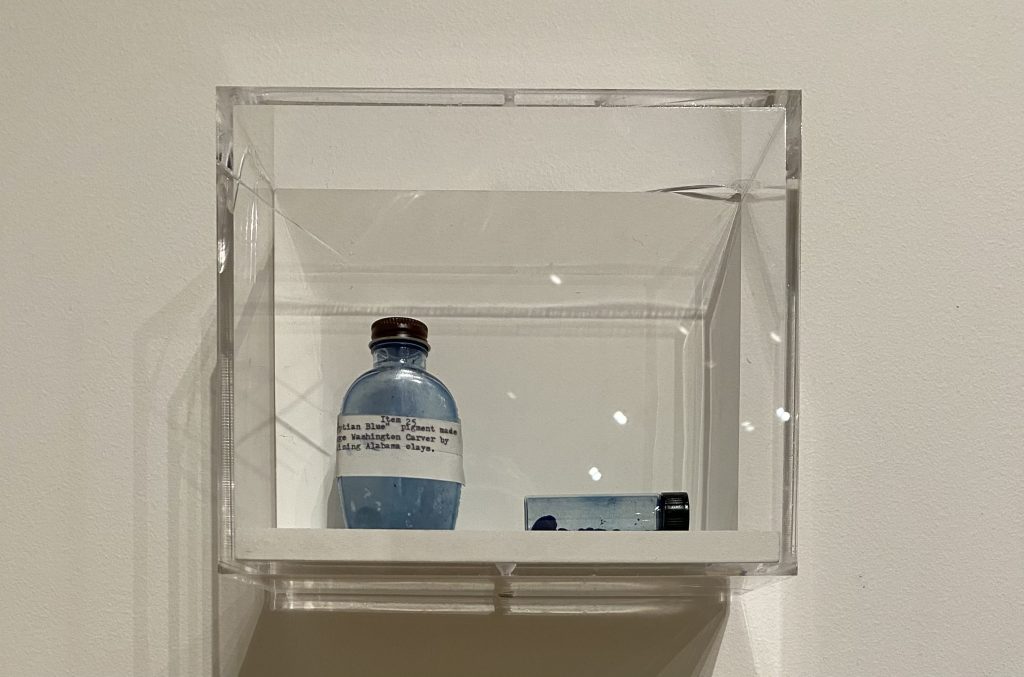

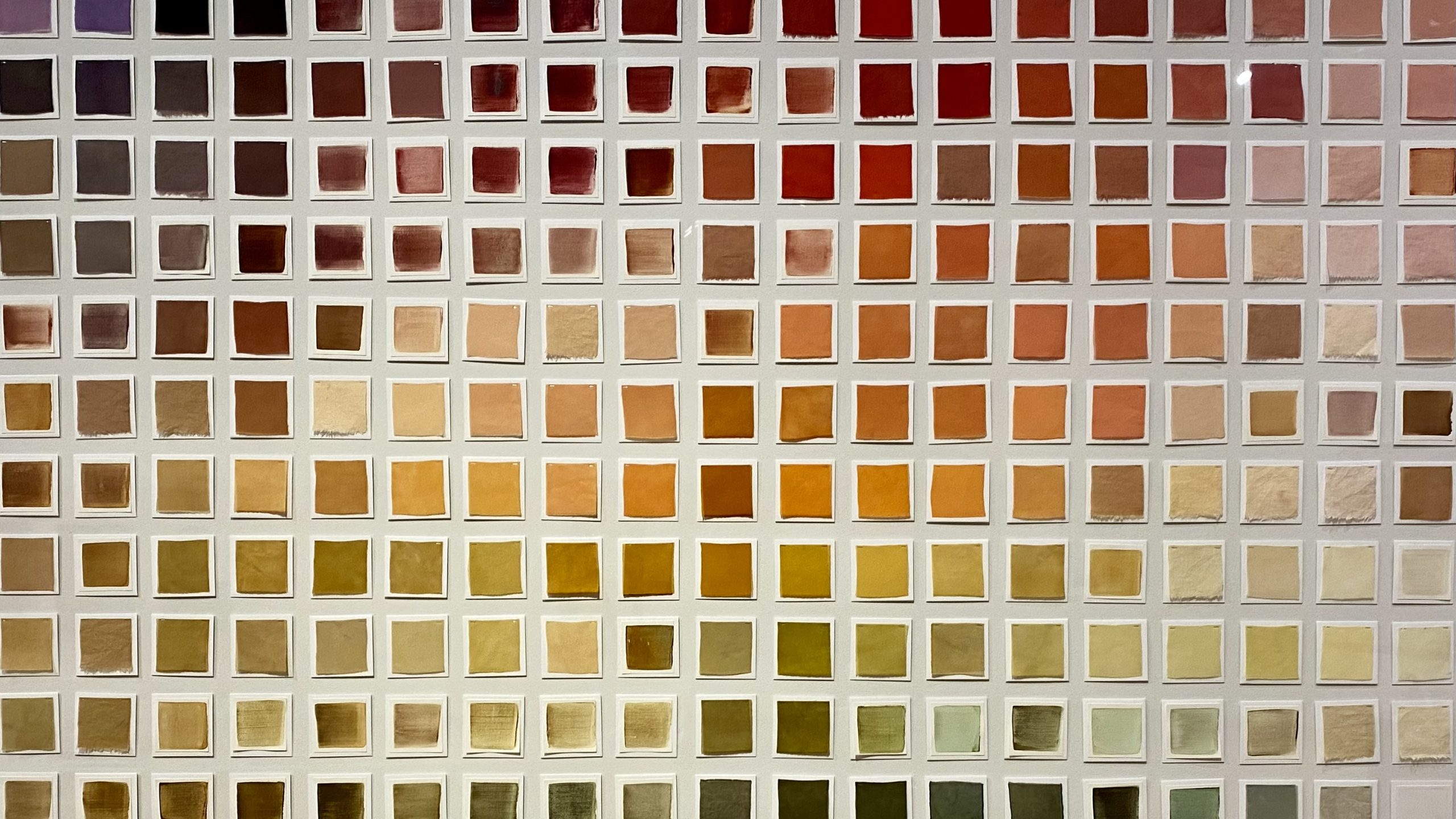

One part of the exhibition that really caught my attention was Julie Beeler’s Mushroom Color Atlas (https://www.mushroomcoloratlas.com). This was my first time encountering the project, and it was captivating to see how many hues can be coaxed from something as humble as a mushroom—soft greens, earthy ochres, unexpected pinks and blues. In the gallery, her work was presented in dialogue with Carver’s own experiments in natural dyes, particularly those he created from peanuts and clay for use in weaving and painting.

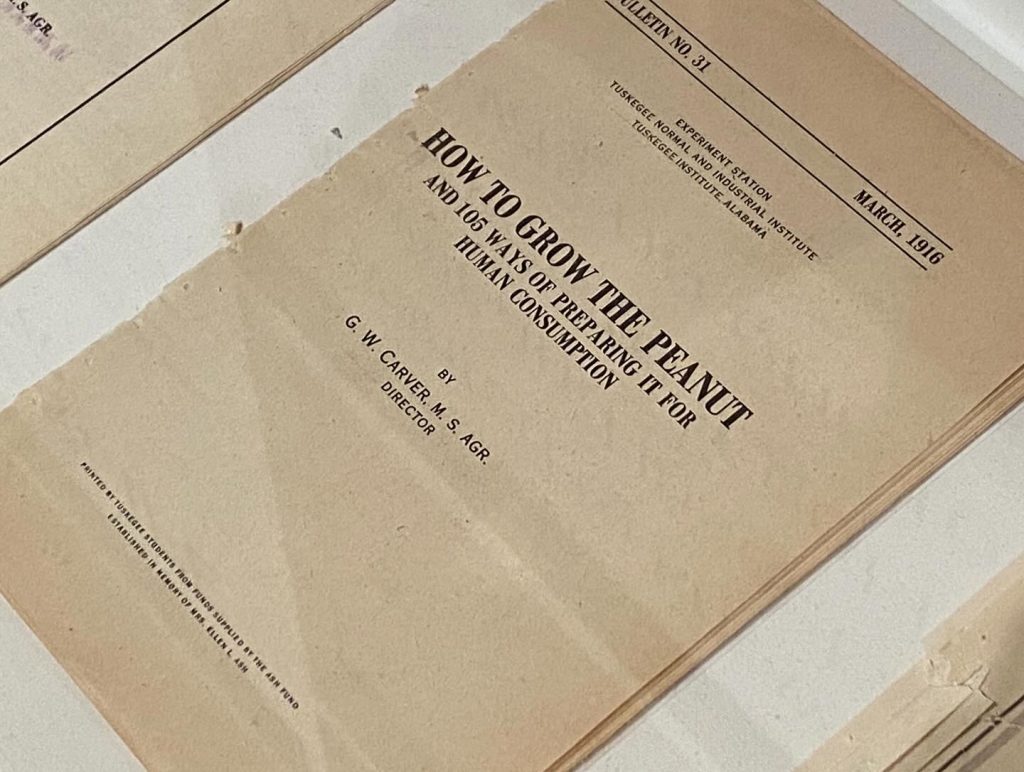

It was a striking curatorial choice. Carver, working in the early 20th century, was a tireless advocate for what we would now call sustainable design: rotating crops to restore soil health, producing natural fertilizers, and experimenting with plant-based materials that could serve as medicines, paints, textiles, or even construction components. He built the “Jesup Wagon,” a mobile classroom that carried tools, samples, and lessons out to farmers across the South. For Carver, design and science weren’t separate domains. They were part of a single mission to make life more equitable, resilient, and beautiful.

World Without End places Carver’s paintings, sketches, and laboratory notebooks alongside the work of a couple dozen or so contemporary artists and collectives who continue to wrestle with the same questions: How do we live responsibly on this planet? How do we align craft, science, and art to create systems that endure? Seeing Beeler’s atlas in this context highlighted the continuity of these ideas. The careful process of extracting color from mushrooms isn’t just an aesthetic exercise—it’s an inquiry into materials, into overlooked natural resources, into the design of a more sustainable future.

Leaving the museum, I kept thinking about color—not just the visual palette of mushrooms, peanuts, and clay, but the broader idea of design as something that must remain rooted in the living world. Carver’s world without end wasn’t about infinite extraction or consumption. It was about cycles, renewal, and design as stewardship.